| 1 |

I Feel Fine |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

A perfect song. John lifted the memorable opening lick from Bobby Parker’s Watch Your Step, and Led Zeppelin, in turn, borrowed it for their tune, Moby Dick. John was a great fan of wordplay, and although I don’t know if he was a student of enjambment — in poetry, a sentence that runs over from one line to the next — he certainly uses it to good effect here. For example, “Baby’s good to me, you know she’s happy as can be, you know / She said so.” The middle eight flows effortlessly into the verse like a car rounding a tight corner while shifting gears: “She’s so glad, she’s tellin’ all the world, that her / Baby buys her things, you know he buys her diamond rings, you know / She said so.” Double enjambment! And of course it starts off with one of the earliest uses of feedback, when John held his guitar pickups next to his amp after Paul plucked the opening bass note. |

| 2 |

Lady Madonna |

Past Masters 2 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Paul wanted to write a Fats Domino boogie-woogie style number. An ode to motherhood, it was inspired by a photo and story he had seen in National Geographic. The tune is infectious. Paul got the honky tonk sound by playing an upright Vertegrand piano, and various sources have long suggested that Paul derived the piano intro from Humphrey Littleton’s Bad Penny Blues, a record which George Martin himself had produced. What seems to be a charming use of kazoos is actually rendered by John and Paul mimicking the kazoo sound by playing the “mouth trumpet.” The real horns are fantastic here, notwithstanding the famous story of Ronnie Scott, who plays the tenor saxophone solo, being irritated that the band provided no written arrangements. In an odd twist of influence, Fats Domino himself later did a very serviceable cover the song. |

| 3 |

She’s A Woman |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This song begins with a fun musical twist. It starts with what sounds like John hitting the down-beats on his guitar; most guitarists would strum on beats 1 and 3 of a 4/4 song. But when the rest of the band comes in, it is revealed that he’s strumming on the off-beats, 2 and 4. (Some guitarists are masters of this technique; it is the trademark sound of Andy Summers of The Police, and you can listen to Man in a Suitcase for an example.) With Paul’s jaunty bass line, it is a nice example of a Jamaican-style ska song. And Paul shows that he can craft some brilliant enjambment of his own: “She will never make me jealous / Gives me all her time, as well as / Lovin’. Don’t ask me why.” George contributes a very bright but understated little solo here, too, with some nice bends. |

| 4 |

Hold Me Tight |

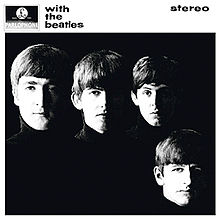

With The Beatles |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This number bounces right along, powered by a driving rhythm and hand claps. The bass line — skipping up and down in thirds — makes it particularly catchy. It was an early Lennon/McCartney effort, so early that the band had played it at The Cavern Club. With its call-and-response, it was intended to be a single, but the Beatles themselves were never very enthusiastic about it. Music critics, too, have not viewed the song very favorably. It’s actually a terrific tune. |

| 5 |

It Won’t Be Long

|

With The Beatles |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Drop the needle on Side 1 of With the Beatles, and the first thing you hear is John belting out the opening line, unaccompanied by instrumentation, before the band and backing vocals instantly join in. John was fascinated with the witty manipulation of language, and he used his gifts here in the opening line: “It won’t be long…til I belong to you.” He’d already done much the same by using two meanings of a single word in the lyrics to Please Please Me. Also noteworthy is the complexity of the melody. The song opens with the chorus — as does She Loves You — and the melody, though written in E, start on its relative minor (C#m). Then the verse alternates between E and C; I-VI is not a characteristic chord change for a rock tune. What’s more, the middle eight makes some equally unpredictable, almost jazzy, turns. But because it all sounds so natural, that complexity is easy to miss. And there’s lots of the characteristic “Yeah” (“Yeah”) back-and-forth between John and the backing vocals of Paul and George. The ending is quite novel, too, with the vocals sliding from the E note up a fifth with falsetto, as the guitars walk down from G to F#, F, and then ending on a lovely Emaj7. All that in just slightly over two minutes. |

| 6 |

I Saw Her Standing There |

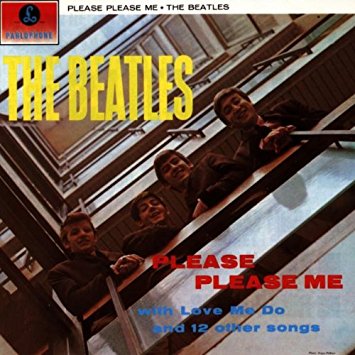

Please Please Me |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This was the first song on the Beatles’ first album, and it’s a grand way to launch it. Paul’s count-off — “One, two, three, FOUR!” — leads into the pulsating combination of throbbing bass line and rhythm guitar. Paul, as he describes it, “pinched” the bass line from Chuck Berry’s I’m Talking About You, a song that the Beatles had been performing at least since their time in Hamburg. (There’s actually a very nice recording of them playing the song in 1962 at the Star Club in the Reeperbahn.) George’s solo relies on the heavy echo that he would use quite often, especially in the early Beatles’ songs. And it ends with one of their signature sounds — four quick notes, followed by a single chord. You can almost see them bowing in unison every time you listen to it. It’s one of a few songs that, I think, are quintessentially The Beatles. |

| 7 |

You Can’t Do That |

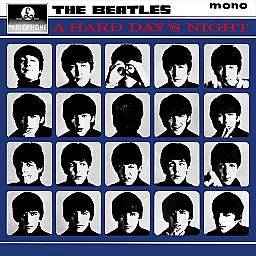

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

John was famously insecure in his relationships with women, and this song reflects his tendency toward jealousy. He penned this bluesy number as a kind of Wilson Pickett tune; indeed, you can hear the obvious similarity in a song like Pickett’s In the Midnight Hour. One of its really distinctive features, as others have noted, is the sharp 9 on the 7th chord at “Because I told you before…” The dominant percussion is Ringo’s cow bell, which is a perfect complement to the song. |

| 8 |

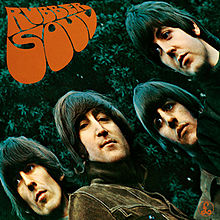

Run For Your Life |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Another of John’s “jealousy” songs, this one is a good bit darker than You Can’t Do That. Its fairly threatening lyrics are belied by a bright melody, and the tight harmonies during the chorus give it an especially happy sound. John lifted the opening line from the last verse of Elvis’s Baby Let’s Play House. The guitar riff between the verses, laid down on top of the rhythm guitar sliding up into the chord, is quite clever, and George offers up one of his better solos for an early Beatles song. The vocal harmonies are really impressive and illustrate just how well the voices of John, Paul, and George fit together. I’ve never discovered where the idea originated, but the decision to sing the word “end” in two syllables — “Catch you with another man, that’s the en-dah” — was brilliant. |

| 9 |

Tell Me Why |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Just like It Won’t Be Long and Please Please Me, this song opens with the chorus. In contrast to those songs, it consists almost entirely of the harmonized vocals of John, Paul, and George. Not only that, the chords for the verse and chorus are exactly the same, and the bridge — which really swings — doesn’t appear until the song is nearly over. (And although John had already written Please Please Me by this point, he seems not to have lost his fascination with the homonym, “pleas” from Bing Crosby’s Please; “Well, I beg you on my bended knees / If you’ll only listen to my pleas.”) The falsetto at “If there’s anything I can do” sounds a little awkward; perhaps it’s double-tracking of John’s voice or maybe he and Paul singing the line together. With the possible exception of Can’t Buy Me Love, it’s the bounciest song on the Hard Day’s Night album. And because it was one of the first Beatles’ songs I ever heard, it’s a sentimental favorite. |

| 10 |

From Me To You |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The song was their second number 1 record, after Please Please Me. Paul later observed that the middle eight of the song — “I’ve got arms that long to hold you…” — was evidence of his and John’s growth as songwriters. And there’s a kind of urgency that builds at the end of those eight bars, with “…and keep you satisfied — Ooooo!” There’s much to admire in this track, aside from the bridge: the harmonica which mimics the opening “da-da dah da-da dum dum dah,” the switch to falsetto on “If there’s anything I can do,” and the song’s unexpected ending on a minor chord. |

| 11 |

In My Life |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

For my money, this is most poignant of all Beatles’ songs. The bittersweet reminiscing combines with a lovely melody and three-part harmony on the vocals. And George Martin stepped outside the control room to play the piano part. John’s lyrics for this song went through a number of drafts, some of which bear almost no resemblance to final version. This is one of only a handful of songs over which there is disputed authorship between John and Paul. John claimed it was almost completely his, with the exception of the middle eight, while Paul recollects that it was more of a total collaboration. Some pretty sophisticated statistical work — see also here — suggests that John’s memory is likely the more accurate. |

| 12 |

Ticket To Ride |

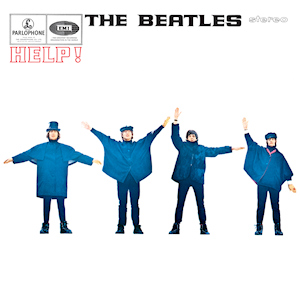

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The title comes from a variation on taking a trip to Ryde, a coastal town on the Isle of Wight. It starts off with the very cool ostinato guitar lick that prevails throughout the song. It’s supplemented with some of Ringo’s best drumming; indeed, Max Weinberg of the E Street Band offers particular praise for Ringo’s innovative approach, and once you’re aware of it, you find that the drumming becomes the song’s defining feature. The switch to double-time during the middle eight and the fade-out was something new for the band. In the Help! movie, it was the soundtrack song for the montage scene on the Austrian ski slopes. |

| 13 |

I Call Your Name |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

John and Paul wrote this song together at John’s house on Menlove Avenue, which was a bit more cramped than Paul’s house on Forthlin Road. (The romantic image of the two sitting directly across from one another and mirroring each other’s guitar playing — John was right-handed and Paul is left-handed — didn’t apply here. Paul later complained that sitting side-by-side at John’s meant that their guitars banged into one another.) The verse starts on E7 and then moves to C#7 and F#7, before resolving to the V chord of B7; that’s a charming chord progression that you don’t typically find in rock songs. The rhythm anticipates, by several months, Ringo’s drums in Ticket to Ride, and the middle eight actually sounds a good bit like the verse in Hold Me Tight. But what I love most about this song is how the lads switch to a swing tempo at the instrumental break after the second verse. George crafts a perfectly-suited solo, which he plays just before it reverts back to a regular rock beat. I’ve read that the song was left off of the Hard Day’s Night album perhaps because of a reluctance to have two songs that featured the cowbell so prominently on the same record. (You Can’t Do That is the other.) Little things make the song great, too, like John’s use of triplets the last time he sings, “I’m not that kind of man,” and the outro, which sounds unusual because, unlike the rest of the song, it alternates between the I and IV chords (E7 and A). |

| 14 |

Eight Days A Week |

Beatles For Sale |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

If you listen to the outtakes on The Beatles Anthology, you can hear how much better the final version is than their early work on the song. That comparison also highlights why it’s such a terrific track; the version they released is much more driving than originally envisioned. My view is not necessarily shared by more sophisticated ears. Commenting on the Anthology outtake, Beatlesologist Alan W. Pollock laments, “The title phrase at the end of each verse is given an outrageous falsetto flip, an idea abandoned, alas.” Personally, I’m grateful that they decided against it. It doesn’t really fit the song, and the “Ooooo”s at the beginning sound equally misplaced. One can judge for oneself, I suppose. The innovation here is the fade-in at the beginning. Paul got the title from a chaffeur, who mentioned how hard he’d been working. |

| 15 |

Back In The USSR |

White Album – A |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This song showcases Paul’s remarkable power as a songwriter. Who would ever think of doing an homage to the Beach Boys and Chuck Berry in the same song? It’s a humorous sendup of Berry’s Back in the USA, and the bridge is a variation on the Beach Boys’ California Girls. (Granted, Mike Love did pitch-in when the song was being written.) There’s even a quick reference to Hoagy Carmichael’s Georgia on My Mind. The opening sound effect is a landing plane, but what few probably notice is that the sound is repeated in the background throughout the entire song. It also has, I think, some of the best lyrics ever committed to vinyl. It includes both consonance (rhymes based on consonants) and assonance (rhymes based on vowels). “Show me round your snow peaked mountains way down south / Take me to your daddy’s farm / Let me hear your balalaikas ringing out / Come and keep your comrade warm.” Paul couples the “k” sounds in “peaked” and “balalaikas.” Likewise, he pairs the “ou” in “south” with same sound in “out,” just as he rhymes the long “e” in “me” with “keep.” And in an earlier verse, Paul also matches “home” with “phone.” Paul loved to belt it out from time to time. Here, just consider the way he repeatedly attacks the word “back.” The song was recorded during the famously unhappy sessions of the White Album; Ringo had temporarily quit the band, and Paul played the drums, making it one of only a handful of songs on which Ringo does not appear. |

| 16 |

Drive My Car |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This bluesy number kicks off Rubber Soul. The little two-measure intro is maddeningly hard to decipher. It’s less hard — not easier, less hard — if you try to listen only to the lead guitar. Paul’s bass doesn’t come in where you’d expect, and it’s not until Ringo’s quick drum fill and first cymbal crash that you start to get your bearings. I was surprised to learn that it was George who suggested the general arrangement of the song, encouraging the band to model it after Otis Redding’s Respect. Once you know what to listen for, the similarity is pretty obvious. John later claimed that they came up with the “Beep beep, beep beep, yeah!” on the fly while recording in the studio. Amazing; I can’t imagine the song without it. If you haven’t seen it, check out the awesome cover of this tune by the MonaLisa Twins.

|

| 17 |

Another Girl |

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

I always associate this song with the image of Paul “playing” the arms of the bikini-clad young woman in the Help! film. Seeing it for the first time as a kid, I thought it was pretty racy stuff. That portion of the film was set in the Bahamas. Ringo explained in the Anthology that, because they were filming in February, it turned out to be quite cold. Similar to It Won’t Be Long — which starts off with a solo line sung by John — this track begins with Paul singing the opening “For I have got…” without any instrumentation. The vocal harmonies are very nice here, but I’ve always been partial to the guitar solo in this song, which, it turns out, was played by Paul, not George, on an Epiphone Casino. The Beatles regarded this song as mere “album filler,” but you can’t help but love it. Paul wrote it while on vacation, in a tiled bathroom in Tunisia. (During the James Cordon “Car Pool Karaoke,” they visited Paul’s old house on Forthlin Road, and Paul pointed out that the bathroom had perfect acoustics for songwriting.) |

| 18 |

The Night Before |

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

I suppose that few would rate this song among the Beatles’ finest, but I’ve always liked it. I think it has one of the best intros in any of their recordings; it builds in anticipation, starting on D7, and then it kinda moves up the scale, staying on 7th chords — Jim Croce’s Bad, Bad Leroy Brown does something similar during the verse — before landing back on the D chord again. It was a great decision to have the backing vocals come in on the last syllable of the verses’ first and third lines and then carry Paul’s lyric to resolution. “We said our good-byes (ahhhh, the night before).” And I like that you can hear George’s voice dominating. When Paul hits the high note at the end of “…makes me wanna cry,” it evokes the early Beatles’ songs where Paul did the famous “head shake” at the mic during live performances (e.g., in She Loves You; “…yeah, she loves you, and you know you should be glad, ooo!“) John played the electric piano quite well in this number, too, and I don’t think the song would have the same appeal if he had stuck to playing rhythm guitar. This was one of the songs filmed for the Salisbury Plain scenes in Help!, and so I can’t discount the possibility that my affection for the song might have something to do with Eleanor Bron — wait for the wink. |

| 19 |

Can’t Buy Me Love |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The first week of April, 1964, the Beatles held the top five positions on the Billboard Hot 100, and this song was number 1. It’s not hard to understand why. As Paul noted years later, “It was a very hooky song.” It was the first song that they recorded that featured only one vocal; it’s all Paul, start to finish. The verse follows a standard blues formula, and it contains perhaps George’s best solo on any Beatles recording. An interesting feature of the song, noted by Alan Pollack, is that the intro has only six measures, where you’d expect eight, while the outro, by contrast, contains the full eight. For me, one of the really fun features of the song is the abrupt half-beat break between “I don’t care too” and “much for money,” something placed in a non-obvious position between “too” and “much.”

|

| 20 |

A Hard Day’s Night |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The most famous opening chord in all of popular music. A good bit of ink has been spilled trying to decipher it; see, for example, here, here, here, here, and here, and those are just online sources. Randy Bachman, of all people, cracked the code during a visit to Abbey Road Studios with the help of George Martin’s son, Giles Martin, who gave him access to the original source recordings. It’s a beautiful thing to hear recreated. Despite its universal recognizability, the song doesn’t really have a chorus — just a four-bar tag at the end of every second verse, but it’s distinctive compared to the rest of the song. It’s a quick little chromatic up-and-down, which plays once and then moves up a step and repeats a second time; “But when I get home to you, I find the thing that you do…” George Martin solos on the piano, and George lays his guitar on top, note for note. Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick reports that the two slowed the playback to half-speed to record their parts, so that when played at normal speed, it would be an octave higher and twice as fast, which is why it sounds so frenetically paced. The fade out — George in a 12-string, I believe — is quite a contrast to the hard bite in the rest of the song. John and Paul wrote it in a single evening, specifically for the movie, only after the movie’s title had been selected.

|

| 21 |

When I Get Home |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

John wrote this song as a kind of blues number, but the choice to end the first line on a minor chord — “I got a whole lotta things to tell her when I get home” — is not at all what one might expect. What stands out to me is the combined rhythm guitar and drum fills just after that line, something that they employ throughout the song as a way to drive into each verse. That same sound appears in the intro to Money (That’s What I Want); since the Beatles did a straightforward cover of Barrett Strong’s original, I suspect they just borrowed it from there, consciously or not, and applied it to this song. In a surprise, the song ends on C, rather than the A minor featured at the end of every other verse. And it’s probably the only rock song that contains the word “trivialities.” |

| 22 |

Old Brown Shoe |

Past Masters 2 |

Harrison |

|

I confess that I never thought much of this song until I heard the Anthology version. It was like hearing it for the first time. George’s voice was more central to the song, the piano’s consistent double-time oom-pah (played by John) made the song more fun, and George’s guitar solo sounded much better than I remembered. That said, I still prefer the original, because Paul’s bass pulls it all together. I’m not sure what they did to get that particular sound, but to me the bass seems heavily compressed and run through some type of fuzz pedal. Paul’s line that runs through the bridge is some of his best work on any Beatles song, and it’s a great complement to George’s vocal. On the whole, the track seems built on the same structure as I Want to Tell You, another George composition. With lines like “I want a short-haired girl who sometimes wears it twice as long,” the lyrics are playful. |

| 23 |

Help! |

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

John wrote this song at a time of relative despair, what he called his “fat Elvis period.” Whatever the motive, it’s a great song. Paul’s principal contribution was the counter-melody that runs behind the verse. I wouldn’t call George’s part a solo, but his little quick walk-down on “Won’t you please, please help me” is first-rate stuff. Like the title song for Hard Day’s Night, the song was commissioned, in the sense that they needed to write a theme song for a movie whose title had already been decided. An interesting bit of trivia: Director Richard Lester was informed that they would encounter copyright problems, since the title “Help” had already been registered. So, inserting the exclamation point was sufficiently distinct to permit the use of the word; it was a practical rather than a creative addition. The footage of them playing the song in the opening scene of the movie — with Leo McKern throwing darts at the projector screen — is good fun, but if you haven’t seen the video of the Beatles Marionettes performing this song, you should watch it.

|

| 24 |

Please Please Me |

Please Please Me |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

When they’d finished recording this song, George Martin was sufficiently confident to predict that it would be their first number 1 song. And he was right. From the opening line, the vocal harmonies are complex. And there’s a delicious contrast after the first and second lines of each verse. After the first line — which is basically just single notes, starting at the second beat, followed by two half notes (and a trill on “my”) — there’s a little giddy-up of half-notes. The second line repeats that same structure and melody, but this time the entire band stops for a single beat before Paul answers with a little bass lick of half notes. And the pre-chorus has a real drive to it, with the call-and-response “Come on (Come on)” that builds up the tension to the chorus. And Ringo’s drum lick leading to the middle eight is genius. The hook was the result of more wordplay from John. He liked the Bing Crosby song, Please, whose opening line was “Please lend your little ear to my pleas,” and he adapted the two-pronged use of the homophone to this number. John later claimed that it was his attempt to write a Roy Orbison song, and although he mentioned Only the Lonely as a possible inspiration, to my ears it seems more likely that a song like Orbison’s Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream) was a model for the song. (Plus, Dream Baby would have been on the radio at the time, having been released only months before John wrote Please Please Me.) If you had to pick a point at which The Beatles were set on a path to superstardom, this song would be it. |

| 25 |

I’m Looking Through You |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Relationships between creative people are often impossible, and in this song, Paul wrote about the difficulty of his romance with the lovely British actress, Jane Asher, at whose family home he was living in 57 Wimpole Street in London. Despite the lyrical despondency — “Love has a nasty habit of disappearing overnight” — the song is an up-beat toe-tapper. When you’ve listened to a song so many times, its oddities are no longer apparent. When I’ve revisited this one, I’ve noticed that it’s maddeningly hard to follow. Paul’s vocal comes in a measure sooner than you’d expect, which makes it sound like a series of pick-up notes (it’s not), and there follows a number of “missing measures” at the end of each verse; trying counting off sets of four measures, and you’ll find that, in the last set before the next verse, there are only three measures. My vinyl version of the song preserves the false starts on the acoustic guitar, something that regrettably has been excised for subsequent digital releases. In a rare variation on traditional roles, Ringo plays the organ(!) on this number, in addition to the drums. George provides some really fine guitar fills between verses. This is one case where I actually prefer the alternate Anthology version. It’s a little slower and omits the bridge, substituting what sounds like a kind of ’60s “swinging London” riff. In reading one of Mark Lewisohn’s books, I was delighted to learn that the world’s only bona fide Beatles historian agrees with me. |

| 26 |

Come Together |

Abbey Road |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The opening track on Abbey Road has got to be one of John’s greatest compositions. It alternates between a soft, bass-heavy line with excellent drum fills and a louder, more insistent rock chorus. John took the opening lyric from Chuck Berry’s You Can’t Catch Me. John’s line was “Here come ol’ flat top / He come groovin’ up slowly,” and Berry’s was “Here come a flat-top / He was movin’ up with me.” This kind of borrowing made sense, since the Beatles were great fans of Chuck Berry, but the similarity was a bit too much for Berry’s music publisher, who sued Lennon for plagiarism. The track certainly bears a strong resemblance to Berry’s song; although Come Together is slower, its verse has much the same rhythm and structure as You Can’t Catch Me. (They settled out of court.) That controversy aside, the song is fabulous. The lyrics, as John himself admitted, are “gobbledygook.” (How does one “shoot Coca-Cola”? Of course, everyone has “feet down below his knees,” but what does it mean to say that he’s “got to be good lookin’, cuz he’s so hard to see”? There are at least a few more probable references, such as “He got muddy water / He one mojo filter.” Although it’s not easy to hear, John is whispering “Shoot me,” at beginning of each line before the verse — a sad bit of irony. On a lighter note, the alternate version on The Beatles Anthology is almost jolly and sounds much more fun than the final cut.

|

| 27 |

Any Time At All |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This song starts with a single shot on the snare drum or what one commentator refers to as “Ringo’s car-door-slam drum accent.” That effect grabs your attention straight away. John, who wrote the song, has the lead vocal, but the second line is unmistakably sung by Paul — most likely because Paul’s vocal range allowed him to hit the higher notes. Especially noteworthy is the way the song moves from the energetic rock chorus to the almost ballad-like verse. During that verse, there’s a very creative chord change. As Allan Pollock explains, it’s “the minor iv chord in a major key.” When it occurs, for example, on “just look into my eyes,” the verse takes a sad turn, which is a sharp divergence from the chorus that follows. There is no middle eight here. Instead, there’s a bridge in which Paul on piano and George on guitar play in unison, mostly in triplets. |

| 28 |

You’re Going To Lose That Girl |

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

A funny formality in the title, since in the recording, John always sings “You’re gonna lose that girl.” The song is a kind of warning that the narrator is about to steal away a potential love interest who’s neglected by someone else. In that sense, it’s similar to She Loves You, another song that, rather unusually, is sung by a man to another man. More than one source suggests that John wrote this song in the style of the Shirelles. I’m not convinced; it doesn’t resemble their best known songs, like Tonight’s the Night or Will You Love Me Tomorrow. But I confess that it does sound similar to their hit, I Met Him On A Sunday. There’s some brilliant vocal arrangement during the middle eight. After the lead line in which John, Paul, and George all sing, “I’ll make a point of taking her away from you,” Paul and George extend the line with “watch what you do.” John tags the “do” with a little “yeah.” The primary percussion is some rapid-fire bongo-playing by Ringo, and George has a short but effective “bendy” solo. In Help!, they are recording this song in a studio, and during the scene, the members of the eastern cult are sawing a circle around Ringo and his drum set from the floor below. I’ve always been puzzled by the close-ups of George and Paul at the microphone. More than once, you can clearly see George’s breath while he’s singing. Was it that cold in the studio? It’s hard to distinguish it from the cigarette smoke, since Ringo smokes like a chimney throughout the entire song. Of course, all four Beatles were heavy smokers then, but George can’t be smoking during the scene, since he’s playing his guitar the entire time.

|

| 29 |

One After 909 |

Let It Be |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Of all the Beatles’ songs, this one perhaps has the most remarkable history. It was one of the earliest songs written by John and Paul, back when they impishly wrote “Another Lennon-McCartney original” at the top of the page. Mark Lewishohn dates the song between 1957 and 1959, which was still the days of The Quarrymen, before the Beatles proper even existed. Despite its early origins, it did not appear on a record until Let It Be, their last released album. Even though they loved the blues, John and Paul almost never wrote standard blues songs. So, this early effort — about a guy who tries to catch his girl at the train station but is mistaken about which train she’s riding — was an exception. There are some very nice early recordings, including one at The Cavern and a studio version on the Anthology, which reveals a straight line drawn from Church Berry’s Roll Over Beethoven to this song. The official recording was a more energetic, live version performed on the rooftop concert in 1969. It’s heartening to think that, on the verge of disintegrating, the Beatles decided to reach back to their earliest days for a bit of nostalgia. You can hear (and see in the Let It Be film) that, despite their personal differences, they were still four guys who genuinely enjoyed playing together. |

| 30 |

Roll Over Beethoven |

With The Beatles |

Berry |

|

George’s breakneck intro sounds more like Chuck Berry than Chuck Berry does, I think. There’s a greater effort at precision in George’s cover than in the Berry original. The same is true of the solo, which is tighter than Berry’s. Of course, since they played it countless times in the various club performances, it makes sense that it would seem second-nature to George by the time they got around to recording it. And on top of his stellar guitar work, George handles the lead vocal. In their first American concert, at the now long-defunct Washington Coliseum, it was their opening number.

|

| 31 |

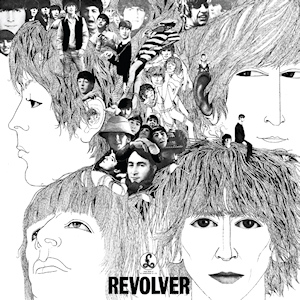

I’m Only Sleeping |

Revolver |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This song was notable for its use of the “backward guitar.” The Beatles had begun to forgo live performance in favor of studio experimentation. After hearing a tape that was accidentally threaded backwards, they decided to incorporate the sound into this track. So George, much to the consternation of engineer Geoff Emerick, agonizingly worked out a solo which, when played backwards, would fit the song. John wrote this number as a reflection of his self-confessed laziness. I’ve never found a source to support my intuition, but I’ve always thought that Paul must have written the bridge; there’s such a dramatic break from the somber, monotonic sound of the verse to the more happy orientation of the “Keeping an eye on the world going by my window.” (Sometimes, it might be obvious where one songwriter stops and another takes over. I have a similar feeling about My Brave Face, which Paul co-wrote with Elvis Costello; the middle eight has Elvis’s fingerprints all over it, compared to the rest of the song.) A technical note: the song was recorded using “vari-speed,” with John’s vocal being recorded slower than normal — and the music recorded faster — and then matched up for the final version. |

| 32 |

Taxman |

Revolver |

Harrison |

|

George crafted this number after he learned the fiscal consequences of the substantial amounts of money the Beatles were earning. At the time, Britain had a tax bracket greater than 90% for the very rich; the Beatles’ tax obligations were 96 pence for every pound, a fact that George in particular found dispiriting. Early drafts show that he had some interesting lyrics that never made the final cut, such as “You may work hard trying to get some bread / You won’t make out before you’re dead.” It’s the lead track on Revolver, and so the first thing one hears is George’s sonorous count-off, which in fact was spliced on later. John and Paul’s vocals are interesting here; at some points they sing the lead lyric, and at others they remain in the background. The result during the bridge is that they sing “If you drive a car-car,”– hitting “car” twice for emphasis — and George finishes the line. That pattern is repeated, with “If you try to sit-sit,” and so on. It is ironic that, on a Harrison composition, it is Paul, not George, who plays the lead guitar. It’s really a kick-ass solo, one of the best on any Beatles recording. According to recording engineer Geoff Emerick, George was not pleased when George Martin suggested that Paul take on this responsibility, but years later he confessed his sincere admiration for Paul’s work and, in particular, its slight Indian vibe, which he regarded as a kind of tribute to George’s growing interest in eastern religious traditions. |

| 33 |

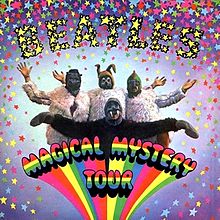

I Am The Walrus |

Magical Mystery Tour |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Although this song is widely regarded as one of John’s best creations, it had a rather ignominious start. Beatles producer George Martin hated it, and for a such an open-minded man who encouraged experimentation, that’s saying something. After hearing John’s initial acoustic rendition, Martin is reported to have told John, “What the hell do you expect me to do with that?” The spare, two-note whine throughout the verses was meant to sound like a police siren (the kind, I suppose, that was characteristic in Britain but not common in the U.S.). In fact, the first lyric John wrote was “Mister city policeman,” to match the sound of the siren. Most of the lyrics are gibberish, and in an echo of Joyce — who claimed that in Ulysses, he “put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries” — John wanted to keep his own analysts equally occupied by writing a song “that has enough little bitties going to keep you interested even a hundred years later.” So, for instance, John tapped the memory of his friend and former Quarrymen member, Pete Shotton, for a line from a playground verse from their childhood (“Yellow matter custard, green slop pie / All mixed together with a dead dog’s eye”), and after adding the reference to “semolina pilchard,” said “Let the fuckers work that one out, Pete.” George Martin worked with John to develop the orchestration, which turned out very well indeed. The overdubbed bass line in particular somehow pulls the song together and makes it less monotonous, and thus more interesting, over and above the melody. A few interesting details: the title is adapted from Lewis Carroll’s poem, The Walrus and the Carpenter; the Egg Man was actually Animals’ lead singer Eric Burdon (and why John Lennon called him that involves a rather naughty story); the background vocalizations (“Everybody’s got one”) were provided by the Mike Sammes Singers; and it’s King Lear (Act IV, Scene VI) during the fade-out. Finally, for those who sometimes think otherwise, it’s “goo goo ga joob,” absolutely not “coo coo ca-choo.”

|

| 34 |

Oh! Darling |

Abbey Road |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

As I’ve noted, for all their love of the blues, the Beatles rarely wrote in a traditional blues format. This track by Paul is an exception. (John’s Yer Blues is another.) Unusual for any Beatles song, it’s written in what feel like 3/4 time (it’s actually 12/8). Paul wanted his voice to sound raw, and he repeatedly tried once a day over a series of days until he got what he was after. He said later that it was “a bit of a belter.” The backing vocals, which are easy to overlook, are quite gentle for an otherwise heavy rocking song. The simple, single one-beat shots on the rhythm guitar work very well. Likewise, George’s (I presume) guitar fills during the middle eight, which I think are just arpeggios, add something special to Paul’s near shouting of the vocal. And the bluesy ending — Bb7 to A7 — is perfect. (But what’s the deal with the exclamation point after “Oh”? Shouldn’t it have been “Oh, Darling!”) |

| 35 |

Think For Yourself |

Rubber Soul |

Harrison |

|

This song is pure George; it couldn’t possibly have been written by anyone else. It was, I think, quite a departure for George, whose songs to that point were pretty standard songwriting. The verse is somewhat disorientating, since it’s not quite clear where the melody is headed. Then it magically transitions to the chorus, and it all makes sense. The lazy fuzz — it sounds like a guitar, but it’s actually Paul’s “fuzz toned” bass — is counterpoised by the precise, regular use of triplets. Not only that, as Alan Pollock notes, the song moves easily between a kind of minor mode in the verse and a major mode in the chorus. What is this song about? George himself claimed that he wasn’t sure. Although it’s not really a characteristic of the song itself, the decision to have it followed by The Word on the Rubber Soul album was inspired, since the two together sound almost like one song in two parts. |

| 36 |

I’ve Just Seen A Face |

Help! |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

A folksy rocker by Paul, probably written about Jane Asher. It has one of the more intriguing Beatles’ intros. It begins with a somber-sounding sequence of A, G#, F# and then suddenly turns happier by moving up an octave, with F#, E, D, and it remains optimistic and upbeat from that point forward. It’s a lovely sequence that I think involves simply sliding up the guitar neck in the same chord pattern, playing some fast triplets. The result sounds a bit like a mandolin. It’s an all-acoustic number, sans bass, with Ringo using brushes on the snare drum. In the entries for I Feel Fine and She’s A Woman, I noted the Beatles’ occasional use of lyrical enjambment — rhymes that run over one line and into the next. In this track, Paul almost makes it an exercise, since every verse, as well as the chorus, is “enjambed.” The lyrics come at you so fast, you might not notice, but it’s there, over and over again. “I can’t forget the time or place / Where we just met. She’s just the girl for me / And I want all the world to see / We’ve met” or “But as it is I’ll dream of her / Tonight…” or “I have never known / The like of this. I’ve been alone…” or “And she keeps callin’ / Me back again.” Paul must enjoy this song. He played it on the Wings Over America album — with the great Denny Laine of The Moody Blues on the 12-string Ovation — and there’s a nice version on his Unplugged album, too.

|

| 37 |

I’ll Cry Instead |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Still more insecurity from John. The lyrics bemoan lost love, wallow in self-pity, and plot revenge. The song has a sweet rockabilly feel, which is evident in John’s a slapback echo on the rhythm guitar. As a supplement, George uses some Scotty Moore-style syncopation at the end of each verse (right after “…only girl I had” and “…people that I meet,” for example). In that respect, the verses in this song closely resemble Elvis’s That’s All Right. The bridge makes quite a turn from the key of G to D, and at its end somehow jumps back to G. You can tell that it’s an odd turn, since John doesn’t so much sing as he speaks the phrase “…again some day,” before heading back to the verse. And there’s a terrific little thumping bass line that Paul plays solo both times that John sings “and show you what your lovin’ man can do.” Speaking of Scotty Moore, there’s a great video of him playing That’s All Right, Money Honey, and Mystery Train with Eric Clapton, in which he showcases some of his trademark guitar style. You can see why George found much to admire. |

| 38 |

Twist and Shout |

Please Please Me |

Medley / Russell |

|

This is one of those songs that many people assume is a Beatles original. It’s actually a cover, first recorded by The Top Notes and subsequently by the Isley Brothers. The Top Notes version bears little resemblance to the Beatles’; it has a very different sound, more akin to, say, The Chiffons’ One Fine Day. The Isleys’ cover is closer to what the Beatles eventually recorded, albeit a bit slower. It’s no surprise that the Beatles version is the best known, since it’s the superior of three. One improvement is John’s decision to pound out the “Come on” four times before each “baby, now.” (The Isleys do this only once, by contrast, and it’s very tentative, almost in the background.) This was a closer to many of the early Beatles shows, since John typically shredded his voice in its performance. George Martin, as well, regarded it as “a real larynx-tearer.” But it’s that raw performance that gives the recording — they could only manage two takes — so much power. It think it’s universally true that, anytime this song is played in crowd, everyone joins in at end for the “aaaah… aaaah… aaaah…” just before the chromatic double-triplet walk-up and final chord. |

| 39 |

Long Tall Sally |

Past Masters 1 |

Johnson/Penniman/Blackwell |

|

The Beatles were crazy about Little Richard, and they were thrilled when they got the chance to play together on the same bill in Liverpool in the fall of 1962. Paul, in particular, relished doing his full-throated imitation of him. (Paul’s father never understood what his son was doing until he heard the real Little Richard singing.) For his part, Little Richard admired their music, as well. He famously said, in one interview in the 1963, “I’ve never heard that sound from English musicians before. Honestly, if I hadn’t seen them with my own eyes I’d have thought they were a colored group from back home.” Their cover of his Long Tall Sally is masterful. Although the Beatles did a faithful rendition of Little Richard’s original, his version is backed by a horn section and features a sax solo. The Beatles, of necessity, relied upon their guitars and some scorching leads. (George Martin played piano on this number.) It’s wonderful that the Beatles kept the original line about Uncle John having “the misery,” but it’s a shame they dropped the reference to “bald-head Sally.” Neither did they mention her being “built for speed” — which also happens to be the title of a great collection (and song) by the Stray Cats. |

| 40 |

I Want To Tell You |

Revolver |

Harrison |

|

John and Paul gave George an unprecedented three songs on Revolver. That’s probably a measure of George’s development as a songwriter. Like Eight Days A Week, it begins atypically with a fade-in, on George’s opening ostinato guitar lick. What follows is a song that’s loaded with peculiarities. Notice, for instance, how George repeatedly slides into the word “tell.” Bealtesologist Alan Pollack complains about the “irritating harping on the E-minor ninth chord in the piano,” but to me that’s one of the best parts of the song. He does at least acknowledge the interesting way in which the slow middle eight is driven back into the verse by the piano. Plus, the fast shake of the tambourine (credited to John) at the end of each verse — which sounds a bit like a rattlesnake — is another cool component of this unusual number. As if that weren’t enough, the ending comes out of nowhere, fading out with Indian-influenced vocals. |

| 41 |

Wait |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Paul claims to have written this number, but for reasons unclear, John ended up with the lead vocal. (Paul takes the lead in the bridge.) George must have used a volume or wah-wah pedal to get the slight variation that brings his guitar in and out of the song when John and Paul half-sing/half-shout “Wait” at the start of the chorus; it’s a nice effect. It’s written as a kind of love letter to a distant sweetheart, and I’ve always liked the way the music seems to match the mood of the lyrics. The minor chord dominate in the verses, in which the narrator laments the pain of their lengthy separation, but the refrain is more hopeful, switching to the relative major chord, and imploring his girl simply to wait until he returns to her side. Several sources suggest that this song was left off of Help! because it was judged to be inferior. |

| 42 |

Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby |

Beatles For Sale |

Perkins |

|

The great Carl Perkins was another idol of the Beatles, and this rockabilly classic had long been in their repertoire. The Beatles respected the “guitar chunk and pause” that Perkins used in the opening lines to some of his songs. “Well, they took some honey,” (guitar / break) “from a tree” (guitar / break), and only then does the song kick into gear with “Dressed it up, and they called it me.” Elvis’s famous cover of Perkins’ Blue Suede Shoes simply runs right over the anticipation that Perkins builds through the use of that same tactic in his original; instead, Elvis just rushes through uninterrupted, “Well, it’s one for the money / Two for the show / Three to get ready…” George’s solos reveal his love for Perkins’ style. And the heavy echo on George’s voice follows the rockabilly tradition, as well. This song is righteous. |

| 43 |

I Should Have Known Better |

Hard Day’s Night |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This song always reminds me of the train scene in Hard Day’s Night in which this number appears. Although it was filmed at Twickenham Studios, the film crew “rocked” the little set to simulate the train’s movement. The lads are in some kind of steel baggage container, sitting with Paul’s grandfather (“Who’s that little old man?”) and a very coy-looking Pattie Boyd, George’s future wife. This is a John tune, one in which he combines both the lead vocal with his harmonica (so one of the two had to be overdubbed, since they are occasionally simultaneous). Of course, he played the harmonica on several early Beatles songs, but this might be his best work on the instrument. It’s not as creative as it is in, say, There’s A Place, but in this track it’s louder and more dominant, played almost like the lead instrument. Indeed, it’s the first thing you hear blaring when the song begins, and John shows some real flair from the get-go. I’ve always liked the way he sings the bridge, “You’re gonna say you love me too-oo-oo-oo-oo, oh-oh” before climbing to the falsetto. The song also featured George on his new Rickenbacker 360/12 Deluxe. It was unique among 12-strings guitars, in that the machine heads were fitted both horizontally and vertically. As a result of this innovation, George said, “even when you’re drunk you can still know what string you’re tuning.” It was a favorite of Tom Petty, as well. |

| 44 |

Blackbird |

White Album – A |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Paul claims to have based this song on Bach’s Bourree in E minor, and I suppose it does sound like a distant cousin. (As far as Bourree itself is concerned, I much prefer the Jethro Tull version.) The man himself breaks it down in this video. Notwithstanding the music’s classical origins, the lyrics are about the civil rights movement in the U.S., with the blackbird symbolizing an archetypal Southern black woman “waiting for [her] moment to be free.” There’s a lovely story often told about how Paul demoed the song by playing it out of an upper window in his London home for the female groupies who routinely gathered outside. To me, it is far more appealing than his other solo acoustic numbers, like Mother Nature’s Son and Yesterday. And it’s not a metronome, as some sources report; it’s Paul tapping his foot. |

| 45 |

I Want To Hold Your Hand |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Capitol Records — which was owned by British EMI –was notoriously stingy about releasing English records in the states, since they were convinced that they would never sell. This song was written specifically to appeal to an American audience, and it became The Beatles first number 1 hit in the U.S. My favorite story about this song comes from Peter Asher, brother of Paul’s then-girlfriend Jane Asher and one half of the British duo, Peter and Gordon. Paul had recently moved into Jane’s parents’ house in London, and John and Paul were in the music room in the basement, where Jane and Peter’s mother occasionally gave oboe lessons. (She was a professor at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.) John and Paul wrote this song together on a upright piano, not on guitar, amazingly enough. When they’d finished, they asked Peter if he’d like to hear a song that they had just written. By Asher’s account, it was thrilling to be the first person to hear this song. (He liked it so much, he asked them to play it twice.) A 15-year-old girl from suburban Washington, DC, named Marsha Albert, lobbied her local radio station to play The Beatles, and the DJ arranged for her to introduce the record on the air, a pirated copy flown over from England in advance of Capitol’s scheduled American release. The response was so phenomenal that Capitol had to move up the record’s release date. The intro pulls the listener in immediately. It’s actually the end of the bridge, where they sing “I can’t hide!” which helps explain why the bridge drives so easily into the verse later in the song. It’s a perfect little rocking love song, and the outro is classic Beatles stuff, as well. |

| 46 |

I’ll Get You |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Unrequited love is hardly a novel idea for a pop song, but the narrator in this song is more determined than most — almost disturbingly so. Musically, it’s pretty standard stuff, and resembles other songs of the same period, such as Little Child. But somehow the component parts taken individually are greater than the song as a whole. The intro has some catchy “oh, yeah”s backed by a simple bass line and hand claps. (Since it was the B-side to She Loves You, the “yeah”s on both sides of the record did not go unnoticed.) The verse skips along happily enough, but then comes the pre-chorus: “It not like me to pretend,” and they make an unexpected shift from D to Am, rather than A. It turns out that was Paul’s decision, lifting the same chord change from Joan Baez’s All My Trials; you can hear it at the end of her first line, “Hush, little baby, don’t you cry.” A number of sources note Paul’s reliance on Baez, and as Paul himself explained in Barry Miles’s book, “It’s a change that had always fascinated me, so I put it in.” Behind those lyrics is a driving insistence to the music that is resolved in the chorus lines. And then the middle eight turns happy again, with some beautiful vocal harmonies and lyrics that rhyme “time,” “mind,” and “resign” (and end with the enjambed line “yourself to me. Oh, yeah.”) Paul still occasionally includes it today in his concerts. |

| 47 |

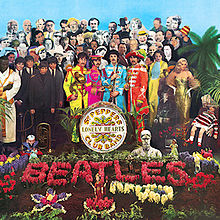

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band |

Sgt. Pepper |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

It’s well known the group decided to develop a “concept album,” built around a set of mythical alter egos. In announcing these personas, the opening number is a kind of bluesy number, the heavy French horns notwithstanding. Paul wrote it at his London home in St. John’s Wood, and it turned out to be quite a rocker. In fact, Geoff Emerick, the Abbey Road engineer, was surprised that the song had such back-to-basics feel to it. Paul played the lead guitar here, and he used much the same sound that he employed for the solo her played on Taxman. There’s a wonderful “Deconstrucing Sgt. Pepper” video, in which you can hear each of the individual tracks to the song. Maybe only interesting to Beatles geeks, but still a fun curiosity. |

| 48 |

No Reply |

Beatles For Sale |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

The slow number was an unusual choice as the opener on the Beatles for Sale album. It tells the story of an unfaithful love who refuses to see her ex. He phones, comes to her house, and even though she’s obviously home, she pretends to be out. John was the principal author, borrowing the idea from the song Silhouettes, by The Rays. It starts with a heavily echoed vocal by John, which inexplicably disappears at the second verse. The song itself has a number of distinctive attributes. It has no chorus, only verses and bridge. Although written in the key of C, the verse starts on the IV and V chords, before ending on C. The plaintive line, “I nearly died,” has a kind of desperation to it. For me, though, it’s the middle eight that makes the song so appealing; when the song gets to the bridge, the tempo switches to a kind of chugging double-time, starting on C but then moving to E and A (“If I were you, I’d realize that I…”). And that’s not just my opinion. Ian MacDonald calls it “among the most exciting thirty seconds in their output.” |

| 49 |

Revolution |

Past Masters 2 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Sure, the lads borrowed from other songwriters in various ways, but the opening of this track is simply a shameless rip-off of Pee Wee Crayton’s Do Unto Others. You can’t tell one from the other. Hell, they’re even in the same key. I’ve never found the politics of the lyrics very illuminating; I actually don’t think I understand them. But it matters little, since this song is just a great rocker. John’s guitar on this track — heavily fuzzed — is some of his most outstanding work. And his little lick that gets repeated at the end of the chorus might be the catchiest part of the song. There’s a live version in which Paul and George do background voice fills with repeated “shoo-be-do-wop”s. Those never made it into the studio version, alas, although they do appear in the acoustic version on the White Album. The piano here is not George Martin, but British keyboardist Nicky Hopkins, who played in a number of memorable songs of the era. That’s him in She’s A Rainbow (Rolling Stones), Getting In Tune (The Who), and Sunny Afternoon (The Kinks). |

| 50 |

Penny Lane |

Magical Mystery Tour |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Paul wrote this song on his “magic piano,” a psychedelic upright, painted by a trio of artists, Douglas Binder, Dudley Edwards, and David Vaughan. (I’ve seen Paul play Lady Madonna on this piano, which I would count as one of my life’s greatest delights.) This song is a delightful nostalgic look back at childhood, in that sense not unlike John’s In My Life. There is lots of lovely imagery, but I’ve always been partial to the “behind the shelter in the middle of a roundabout.” Paul’s happy optimism shines throughout the song, without a trace of irony. The piano style worked well for Paul in this song. Indeed, Ian MacDonald notes how it reappears in other songs, such as Fixing A Hole, Getting Better, With A Little Help From My Friends, and Your Mother Should Know. The bell after “clean machine,” the piccolo trumpet, and the clever melodic shift after “meanwhile back” are among the nice touches in the song. Small bits of trivia: This song and Strawberry Fields Forever were released as a single, with both songs as the A-side. And the barber shop was called Bioletti’s. |

| 51 |

Paperback Writer |

Past Masters 2 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

By the time this song was recorded, it was clear that the Beatles wanted to give up touring and concentrate on innovation in the studio. Their efforts in this track reflect that. There are richly dense, overlapping vocal harmonies that couldn’t be replicated on stage. (Not that they didn’t try, with less than stellar results.) Paul swapped out his customary hollow-body Hofner bass for a solid-body Rickenbacker 4001S — which he favored in late-Beatles recordings as well as his early solo work — recorded with a reverse-engineered speaker acting as a microphone. (Emerick’s book tells that story in much greater detail.) After the acapella vocal intro and very slight snare strike from Ringo, Paul (not George) launches into the memorable guitar lick that drives the song. Like, say, Drive My Car, it tells the story of a career ambition, and I think I’m right in saying that it’s the Beatles’ only epistolary song (“Dear Sir (or Madam), Will you read my book?”). In fact, Paul wrote out the lyrics in the form of a letter, signed by one Ian Iachimoe. (Gold star to those who know the origin of the name.) If you listen closely to the background vocals on the third and fourth verses, you can hear that John and George are singing “Frere Jacques.”

|

| 52 |

She Said She Said |

Revolver |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This is probably the most “revolvery” song on Revolver. It’s a great track that seems to capture the spirit of the record, which was a major creative step up from Rubber Soul. As is widely known, John wrote the song after an LSD-fueled encounter with Peter Fonda at a party in Los Angeles, in which Fonda kept telling John, “I know what it’s like to be dead.” (Don’t do drugs, kids.) John softened the song by changing the character to a woman. It’s perhaps fitting that Paul, who was very hesitant about acid use, doesn’t appear on the song. John and George combine perfectly for this one. During the verse (especially the second and third verses), Ringo’s drums clearly echo his catchy but unusual phrasing found in Ticket to Ride. But drumming over the bridge couldn’t have been easy; although it is a brilliant bit of song writing, it has a maddening time signature. Alan Pollack’s essay breaks it down, line by line, with each number representing the number of beats per measure: [4 + 4] [3 + 3 + 3] [6 + 3] [6 + 3]. Try it out; it’s like someone showing you how to solve a puzzle. |

| 53 |

Strawberry Fields Forever |

Magical Mystery Tour |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Written ostensibly about a Salvation Army foster home in Liverpool, the song is largely a reflection of John’s feeling of differentness and being disconnected from the world. It’s clearly one the group’s best. Paul plays the Mellotron intro, which provided the memorable flute-sounding intro, and then the song descends into psychedelic sounds and imagery. Most Beatles fans know the wonderful story about the recording of this song. After several takes, John asked George Martin to write a score for strings to accompany the song. Martin recorded the orchestral part slightly faster and in the key of C major, while John’s taped vocal track with the band was slightly slower and in the key of A major. John wanted them spliced together, but Martin pointed out the obvious problem: they were recorded at different speeds and in different keys. John simply said, “You can fix it, George” — and left the studio. In a happy accident, Martin and engineer Emerick discovered that by slowing one tape and speeding up the other, they could match the two almost perfectly, both in tempo and key (Bb). (This accounts for the odd sound of John’s vocal.) One partial take, which appears on the Anthology, is quite different — and actually quite beautiful — emphasizing John’s simple rhythm guitar. That take also gives weight to George’s use of slide guitar, which would become characteristic of his playing, both with the Beatles (e.g., For You Blue) and on in his own (e.g., Crackerbox Palace). An interesting innovation was the fade-out/fade-in at the end, which they employed again in Helter Skelter. |

| 54 |

Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite |

Sgt. Pepper |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

John got the idea for this song from an old Victorian poster, taking many of the lyrics directly from its advertisement for a mid-19th century circus. Paul asserts that he a small hand in writing it, too. Whatever their relative contributions, I think of this song as George Martin’s, whose keyboards and calliope/fairground sounds give the song its real character. The anachronistic language, with references to “somersets,” “hoops and garters,” and “hogshead,” also gives the track a kind of specific historical context. And use of various characters is unique, at least for John. Paul was the one more likely to dream up imaginary personages for his songs. But Pablo Fanque was a real person, the first black owner of a circus in Britain. The song does have a carnival-like melody to it, but in some ways — and this may sound odd — it reminds me of Norwegian Wood. Both composed by John, they stake out an interval of notes and move up or down the scale, as the case may be. The song gave us one of the most memorable lyrical lines in the Beatles catalogue: “A splendid time is guaranteed for all.” |

| 55 |

I’m A Loser |

Beatles For Sale |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This is one of John’s better executions of witty lyrics, giving the word “loser” a double meaning — someone who simultaneously is an unfortunate sod and a person who has squandered a romantic relationship. John announces his status from the opening line, backed by some very rich vocal harmonies on the word “loser.” And because the vocals here are free form, starting on Am7, the listener is apt to regard this as the intro to a fairly sad song. But it immediately picks up steam, and as soon as we get the refrain, which turns out to be an up-tempo repeat of the opening lines, this number proves to be quite a swinger. In an odd choice, John seemingly reaches to the bottom of his vocal range during the verse, singing a very low G note on the words “crossed,” “end,” “frown,” “cry,” “late,” and “all.” If he’s demonstrating the metaphorical depths to which he has sunk, he lifts himself back up for the chorus, jumping almost two octaves to sing the E in “I’m a lo-ser.” His harmonica sounds a little labored, but it seems to fit the song. And George’s little syncopated solo is one of my favorites. |

| 56 |

All My Loving |

With The Beatles |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This is one of Paul’s best early Beatles songs. It was novel, he has explained, in that he wrote the lyrics first, which was not his regular practice. It’s a happy love song about reassurance of long-distance devotion, penned for Jane Asher. Some suggest that John’s rhythm guitar of fast, repeated triplets intentionally mimicked the sound of Da Doo Ron Ron, which was a contemporaneous hit by The Crystals. Whether that ‘s true or not, he did an amazing job. I’ve always been amazed at how he was able to play that part with such speed and control over the entire song. George’s solo is first-rate, too; he sounds young, fresh, and eager. Some have argued that Paul stole the principal melody from Kathy’s Waltz by Dave Brubeck, a song from my all-time favorite jazz album, Time Out. Indeed, for years I’ve found myself silently (and unconsciously) singing All My Loving when listening to this Brubeck track. Still, the possibility of outright theft seems to me to be unlikely. Strangely, Mark Lewisohn’s book on the Beatles’ sessions reports that “All My Loving was the final song recorded [30 July 1963]. The Beatles recorded 13 takes, numbered 1-14; there was no take five.” Coincidence? |

| 57 |

Revolution 1 |

White Album – B |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This is the slower, more relaxed version of the heavy-rocking B-side to Hey Jude. Although I prefer the other recording, this one does have the “shoo-be-do-wop”s, as well as an interesting use of a small horn section. And there are some very pleasant vocal harmonies here, too (e.g., the “We-ell, you know”s in the second half of the song). A modified version of the opening electric riff from the up-tempo Revolution appears here, played almost in slow motion, but after that, the acoustic guitar dominates the song. The title is revealing; this version of the song was actually recorded first, and the more popular, garage-like rendering came a bit later. |

| 58 |

Day Tripper |

Past Masters 2 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Is there any more recognizable opening guitar lick in the Beatles’ songbook? Perhaps because John’s two little syncopated measures are so ingrained, most people probably don’t regard it as much of a puzzler. But, until Ringo provides the steady of rhythm with the tambourine, which starts on the off-beat, it not clear where the song is headed. Further complicating is that Paul’s vocal comes in a measure too soon (or too late, depending on one’s perspective), but he “corrects” it in the second verse. There isn’t really a middle-eight here, just an instrumental break. Notice that, during that break, there’s a kind of throwback to Twist and Shout, as they build up the tension with a succession of harmonized “Ahhh”s on top of the repeated guitar riff, which by this point the listener understands and has come to expect. John reported that he and Paul dashed this number of quickly, under pressure — other songwriters should be so lucky — and it was released a “double A-side” single, with We Can Work It Out. |

| 59 |

Lovely Rita |

Sgt. Pepper |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Paul was amused to learn that, in the United States, traffic wardens were referred to as meter maids and decided to write this song about an imaginary character named Rita. (The name was a close rhyme to “meter.”) It leads off with Paul’s ethereal vocal intro, followed by four measures of the backing vocals that seem to jump to quickly into the verse; one senses that there will be another four measures, but instead it drops into a zippy melody that double-times the intro. The instrumentation in this track has a rambling echo, highlighted with a kind of electric kazoo sound (Alan Pollack calls it a “synthesized kazoo”). And George Martin contributes the fast, honky-tonk piano solo. Against all that, the backing vocals remaining floating above the melody, which creates a nice effect. The last thirty seconds take an odd turn, when the song, which is mainly in E, shifts to Am with some quite odd vocalization from Paul and John, ending with John inexplicably saying “Leave it.” Lyrically, the idea of “sitting on the sofa with a sister or two” conveys a great image of practical difficulties of wooing the young woman. A draft of the lyrics include Paul’s doodle of the narrator being confronted by Rita, who is ticketing his car. |

| 60 |

And Your Bird Can Sing |

Revolver |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

If you listen to the outtake on the Anthology, you get a sense of the considerable debt the band owes to The Byrds for this song. Written by John, the song may have been intended as a kind of tongue-in-cheek homage (Bird / Byrds) to a group of American contemporaries whom the Beatles much admired. Roger McGuinn’s signature jangly guitars are at the center of this alternate version. The commercially released version features some dazzling harmonized guitar solos by George and (probably) Paul, which make an especially fine and complex complement to John’s vocal during the middle eight. This kind of parallel guitar work anticipates groups like The Allman Brothers, who made it a central feature of their sounds. The sudden appearance of additional vocal harmonies in the first line of the last verse (“You tell me that you heard every sound there is”) is a delightful surprise. |

| 61 |

The Word |

Rubber Soul |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Some groups, like The Smithereens, are famous for covering the Beatles; their Meet The Smithereens is a brilliant piece of work. In 2016, Netflix announced it would be producing an animated children’s show, The Beat Bugs, featuring a number of renditions of Beatles songs. The Shins, a Portland-based indie group, performed this song, which gets my vote for the best cover of any Beatles song. To be honest, I think The Shins’ version is actually better than the Beatles’. Even though the song is true to the original, the harmonies have more depth and are more precise, and the rhythm guitar is superior, as well. (The only downside is the kids’ voices occasionally yelling “Love!” in the background.) |

| 62 |

She Loves You |

Past Masters 1 |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Still the Beatles’ best-selling British single, this song is certainly one of the catchiest songs John and Paul wrote. Written in June 1963 at the Turk’s Head Hotel before a show in Newcastle, the song drew its inspiration from Bobby Rydell’s song, Forget Him; like Rydell’s number, it is written in third person. But where Rydell’s narrator urges a girl to abandon her beau, these lyrics encourage a male friend to patch up his relationship with love-worthy young lady. That’s a strange choice for a pop song, but it matters little since listeners tend to focus on what makes the song so great — “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” (There’s a famous story of Paul’s dad dismissing the informality of the line and encouraging them to substitute “yes, yes, yes.”) George echos the line throughout the song, after every “can’t be bad” (G, F#, E). Although it is easily overlooked, Ringo’s quick tom-tom fill kicks the song into high gear, and then, like only a few other of their melodies, it begins on the refrain. It also has the iconic line that drove the girls wild during Beatlemania, “And you know you should be glad, Ooooo!” Some authorities credit a bit of influence to Buddy Holly‘s use of vocal hiccups in words like “yesterday-ee-ay” and “say-ee-ay.” And it ends on a beautiful a capella G6 chord. George Martin was not crazy about it, but it turned out to be an inspired closing. |

| 63 |

Baby’s in Black |

Beatles For Sale |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

i doubt that this song would rank very high on most fan lists, but I’ve always had a special fondness for it. It has a kind country twang to it, reinforced by the 3/4 time signature in which the Beatles rarely wrote. A principal influence was probably James Ray’s terrific bluesy waltz, “If You’ve Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody,” which was part of the their early repertoire. The subject of the song is a bit morose, and some have suggested it may have been written in reference to Astrid Kirchherr, the young German photographer who befriended the lads during their early days in Hamburg and who is often credited with cutting their hair into their iconic moptop style. She had been engaged to Stuart Sutcliffe, the Beatles’ original bassist, and he died of a cerebral hemmorhage at only 21. John and Paul’s lovely, plaintive line at the start of the bridge — “Oh, how long will it take, ’til she sees the mistake she has made” — always gives me goosebumps. In Barry Miles’ book, Paul cites that middle eight as one of those instances in which John and Paul didn’t really distinguish the lead from the harmony; “You could actually take either,” he said. George’s waltzing guitar solo is one of his best among the Beatles’ early records. |

| 64 |

Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds |

Sgt. Pepper |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Ok, let’s put to rest the most often repeated erroneous belief about this song: It is not a thinly-veiled reference to LSD. Sure, it has a psychedelic feel, but it really was sparked by a school drawing brought home by young Julian Lennon, who was inspired by his nursery school classmate, Lucy O’Donnell. Each of the principals — John, his then-wife Cynthia, and Julian — confirms this. The origin doesn’t really matter, though; regardless of the motivation, it is a highly affecting journey through a series of surreal images and is a testament to John’s power as a songwriter. He crafted most the lyrics, but in The Anthology, Paul reports that he contributed the highly memorable “cellophane flowers” and “newspaper taxis.” The ostinato opening is played by Paul on a Lowery Heritage Deluxe DSO organ, voiced to sound like a harpsichord. In addition to his regular guitar work on the song, George also plays the Indian tambura. You can hear its distinctive droning sound underneath John’s vocal when he sings, “Picture yourself on a train in a station with plasticine porters with looking glass ties.” The song moves back and forth between 3/4 (or 6/8) time in the verse and 4/4 time in the chorus. And interestingly, the chorus itself is only seven measures long, when your ears are expecting another four beats before returning to the verse. As a side note, the vocals were recorded using varispeed, which gives them a slightly higher pitch than normal. The song got a great reboot in 1974, when Elton John’s cover of the song went to Number 1 in the U.S. It was later included as a bonus track on the reissue of the Captain Fantastic album. |

| 65 |

She Came In Through The Bathroom Window |

Abbey Road |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

Young female fans would often station themselves in various locations in the hopes of catching a glimpse of the Beatles. The band referred to them as “Apple scruffs,” and George wrote an affectionate song about them, which appeared on his All Things Must Pass. One group of overzealous admirer’s once found a ladder and entered Paul’s London house on Cavendish Avenue — through the bathroom window. The event is generally believed to have been the germ of the idea for the song. The Let It Be sessions show that the number was fairly fleshed out before they began recording the Abbey Road album, and the Anthology outtake is quite different but no less appealing; it’s a slightly slower, more bluesy version, one that’s less hard-driving than the final product. Musically, it follows a seemingly simple I-IV chord progression in the verse, but the chorus modulates from A to C, which produces the unusual transition at the end, “Tuesday’s on the phone to me” (C) “oh, yeah” (A). |

| 66 |

You Really Got A Hold On Me |

With The Beatles |

Robinson |

|

The Beatles’ version of this Miracles’ classic is a fairly faithful cover of the original, sans the horns, with George Martin on the piano. Two-part harmonies were usually handled by John and Paul, and when George joined, it was almost always as a third supporting vocal. Here, however, John and George pair up as the principal singers. The isolated vocal track shows how nicely their voices compliment one another. Paul drops in occasionally for the high harmonies (see, e.g., the last “Baby! I love you, and all I want you to do”). The song was written by Smokey Robinson, who was looking to craft something similar to Bring It On Home To Me, by the great Sam Cooke; those two songs have a very similar structure, written in a slow 4/4 with rhythmic triplets on every beat. It may just be happenstance, but Sam Cooke’s 1962 song is heavy with “yeah, yeah, yeah”s, which may have been an unconscious influence when the lads wrote She Loves You the following year. |

| 67 |

I’ve Got A Feeling |

Let It Be |

Lennon / McCartney |

|

This tune is actually a mash-up of two song fragments, one by John and the other by Paul. It was perhaps the last time that the two genuinely collaborated in writing a song. They already had some success in merging bits of their own songs into one; A Day In The Life is the most successful example. John had been working on a number entitled Everybody Had A Hard Year — it had indeed been a difficult year for him; divorcing Cynthia, suffering from a heroin addiction, being busted for drug possession — and he borrowed the guitar opening from an unreleased song entitled Watching Rainbows. It’s a nice little blues number, and in the middle eight, Paul belts out the lyric with the kind of gusto that he hadn’t really displayed since the early days of the group. During the last time through the verse, John and Paul lay their respective lyrics on top of each other, singing their respective song fragments simultaneously. |

| 68 |

Not A Second Time |

With The Beatles |

Lennon / McCartney |

|